Monthly Leader Spotlight – Trevor Gardner (Leading in the Belly of the Beast)

What does it mean to lead in the belly of the beast, and what do you do about it? Hear what Trevor Gardner has learned through his leadership and teaching experience.

This is the first of 8 Leader Spotlights, all focusing on leadership in an oppressive system. These 8 leaders and I are working on a book about leading for social justice, due to release in 2020. Each month, I will feature one brave leader, and give space for them to share their reflections, inspirations, and preview of their chapter.

Trevor Gardner: Director of Teaching and Learning, ARISE High School

When did you realize you were in the beast?

This is my 20th year as a public educator in the Bay, seven of those as a high school history and English teacher in San Francisco and thirteen in Oakland, ten as a classroom teacher and the past three as a school leader. About half of that time I worked in district public schools – SFUSD and OUSD – and about half in public charter schools. I have worked in the belly of the beast for a long time and, although my awareness and analysis of the beast is continually unfolding and deepening, I first learned very early in my career that the work I had chosen was a battle that would never be easy.

When I was 22 years old, still existing almost entirely in the bubble of whiteness in which I grew up, I moved to San Francisco and, after applying to be a substitute teacher in the district, fell into a full-time position teaching history at Hilltop High School, a special services school for pregnant and parenting teens in the Mission district. I did not think to question why I, a clearly unqualified, even if eager, young white man who had no experience in the community or with the students there, was given the job and the responsibility of educating young people who were the most deserving of a highly qualified, experienced, and culturally competent teacher. I only knew that I was replacing a teacher who was leaving mid-year for a position in another school district and Hilltop needed to find someone immediately to take over his classroom.

Such is the norm in public education. Consistently, even systematically, the least qualified and least experienced teachers are placed in the classrooms where the needs are the highest, and these classrooms are almost always filled with students of color. Talk about the beast!

On day one, I stepped into a classroom full of Black, Latinx, and Southeast Asian students, an outsider in a world that was distant from anything I knew but where I was positioned in a place of authority. I did not have the historical and sociopolitical awareness to understand, beyond a superficial analysis of racial and economic segregation, the make up of my classroom. I knew little about the lives, cultures, and experiences of the young women who stared up at me in the front of the room. I was not prepared for this undertaking in any way.

Still, from his first day, I could sense a deep paradox held within the walls of this space that would be my second home for years to come. Here, the beautiful and vivacious spirits of my students overflowed with joy and energy while, at the same time, they carried the suffering and struggle of a society that treated their lives as through they did not matter. I did not have the tools or language to analyze this dynamic at the time but I could feel it in my being.

Layered within this paradox that I experienced as a young educator is also the paradox of the emergence of racial consciousness for white educators, who burden communities of color with their ignorance of systems of racism and white supremacy as they rely on their students, families, and other educators of color to bring them to awareness, a burden that is fundamentally not their responsibility but that they take on every day in schools and classrooms across the country.

I had no clue at the time, but my stepping into the classroom at Hilltop would be the beginning of my journey of racial consciousness development: interrogating my whiteness and how it played out in every experience and interaction I had as an educator, understanding the pervasiveness and destructiveness of systemic racism and oppression, and reflecting honestly on how these forces contributed to my own racism, then committing to the lifelong work of challenging, dismantling, and rebuilding these forces both internally and out in the world. This work continues to define, challenge, inspire, and confound me as an educator and as an individual dedicated to awakening in a nation stuck in the “the Dream of living white” described so deftly by Ta-Nehisi Coates in his memoir Between the World and Me.

Chapter Summary – Leading While White

You must understand that in the attempt to correct so many generations of bad faith and cruelty, when it is operation not only in the classroom but in society, you will meet the most fantastic, the most brutal, and the most determined resistance. There is no point in pretending this won’t happen. – James Baldwin, 1963

The nature of the beast is to place educators under conditions where it is impossible to be successful at all the things they are responsible for doing with and for their students. It eats them up. They look for blame. Why is this work so hard? Why is it constantly overwhelming? The beast is effective because it is so pervasive that it can be invisible.

I believe that one of the fundamental challenges of school leadership is getting the educators in a school to identify and understand the beast and to build a sense of solidarity in the face of what James Baldwin aptly names, “the most fantastic, the most brutal, and the most determined resistance.”

To be a transformational school leader in the belly of the beast requires, above all, community, solidarity, and purpose. Furthermore, this purpose must be understood in the context of an educational system set up to maintain our economic, social, and racial status quo, a system that demands that many of our students fail. My chapter will examine how I learned the hard way about what happens when leaders forget to inspire their schools through a shared purpose and a sense of community and how I have worked to place Mission and Vision at the forefront of my leadership while developing a set of Core Values that keep me grounded in the pursuit of this Mission and Vision. By keeping everyone connected to their sense of purpose and guiding them to see/feel its interdependence with the school’s Mission and Vision, I continually work to build awareness that teachers are part of a movement working in solidarity with each other, students, families, and the broader community to dismantle educational inequities and injustices; and that they are not simply individual educators working in an overwhelming and ujust institution.

What keeps you from being devoured? Why stay in this work?

- I stay because I love the work and it brings me joy. Even though I am often exhausted, overwhelmed, and heart-broken, there is no work I would rather be doing. There is nothing that feels as important. I stay because I am inspired every day by the brilliant, resilient, funny, interesting young people I have the privilege of being surrounded by.

- I stay because it is my responsibility. I stay because students in Oakland deserve dedicated, experienced teachers and leaders. To push it a little deeper, I stay because it would be so easy for me to leave. As a middle class white man who did not grow up in Oakland, I hold so many layers of privilege that have brought me to this work. I have the ability and the option to leave at any time – and I have seen hundreds of fellow educators leave throughout the years. But our students do not have this option; they are stuck in the belly of the beast. I stay because I truly believe that our liberation is bound together.

Which leader has most influenced your work?

I really don’t like using the word “blessed” to describe myself; it’s just too loaded of a term. But I cannot think of a better word to describe my journey as an educator. For the past 20 years, I have been blessed to be led, mentored, supported, and taught by so many incredible people I cannot possibly capture them here. So I’ll just briefly mention a few:

- Patricia Keehan was my first model teacher and mentor when I first started teaching at Hilltop High School. She taught me that if you don’t teach from the heart, you don’t belong in this work. She also showed me what it looked like for an educator who didn’t look like her students to teach and serve them like they were her own children.

- Mark Salinas, Allison Rowland, Kevin Hartzog, Pirette McKamey, Robert Roth, Jesse Madway, Chuck Raznikov, and so many others at Thurgood Marshall Academic High School taught me to expect more of my students than I thought I could.

- I had the illuminating privilege of spending two years in a critical inquiry group with my fellow teachers at East Oakland Community High School: Daneen Keaton, K. Wayne Yang, David Philoxene, Ketia Brown, Cesar Cruz, and Jeff Duncan-Andrade. They pushed me to love my students and to turn inward and reflect critically in order to be a critical pedagogue.

- Perhaps the most effective leadership team I have ever worked for was the combination of Samuel Butcher and Matthew Zito at Thurgood Marshall. Dr. Butcher was the visionary and the moral leader of the school and Zito was the magician who put all the pieces together and made them work. The two of them were able to build a dream team of inspired educators who created a truly transformative school for thousands of students in San Francisco’s Bayview/Hunter’s Point neighborhood (until this beloved school fell prey to the beast).

What are you reading these days?

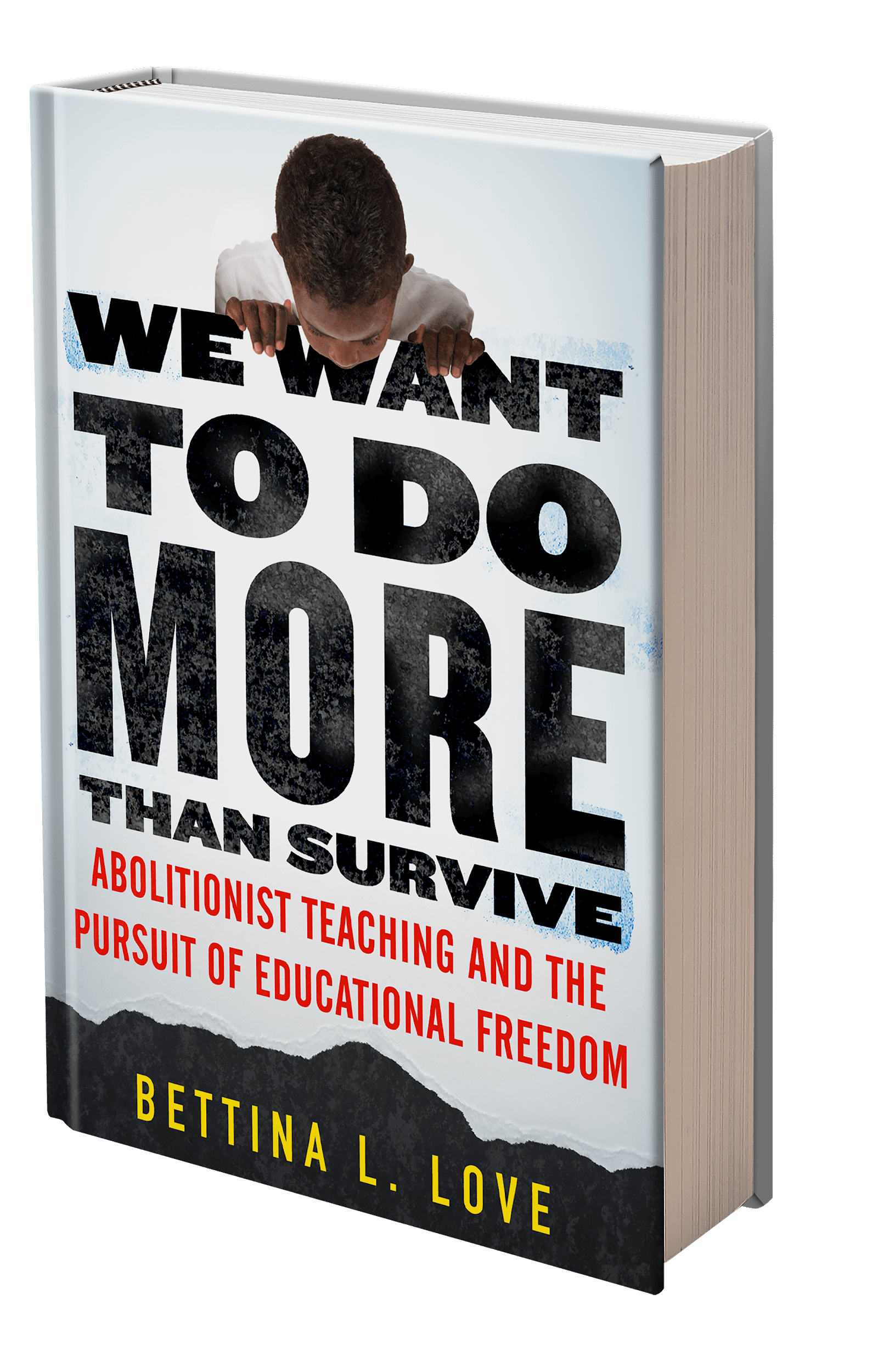

Stop what you’re doing and get a copy of We Want to Do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom by Bettina L. Love. It is a paradigm shifter that examines and castigates what she terms the “educational survival complex”, a set of systems, structures, and pedagogies that, despite at least some positive efforts and good intentions, maintain the status quo of white supremacy, patriarchy, and inequity. It was a serious gut check for me when she introduced the term “spirit murder” for what so many of our young people experience in our schools every day because, both as a teacher and a leader, I know I have engaged in some of these behaviors.

Links or Resources

Discipline Over Punishment by Trevor Gardner (published by Rowman and Littlefield Publishers)