6 Habits of Highly Innovative Schools – Book Review – The Power of Habit

We usually think of change as big, overwhelming, and insurmountable. This might be the addition of graduation portfolios, raising reading scores, or addressing Social Emotional Learning standards. This feels more than you have time, energy, or resources for. So why try? Because, with culturally responsive leadership, change can start small.

Very small.

You just have to break it down.

Into habits.

The Power of Habit

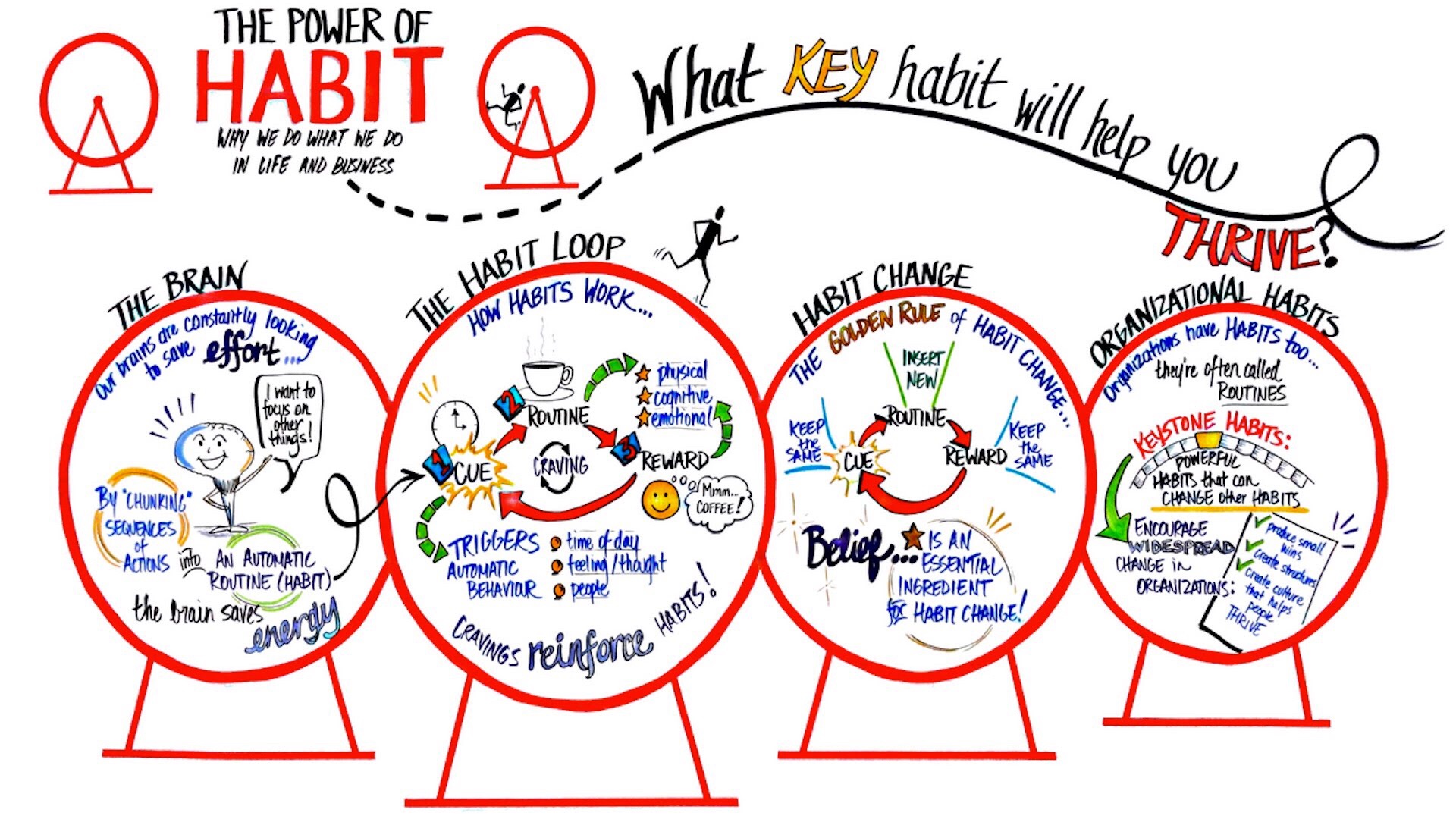

Charles Duhigg, in his book The Power of Habit, talks about what makes people, businesses, and organizations successful. No reason we can’t apply some of this to schools, where we most definitely need more success. Especially for our students of color and our low-income students. One concept Duhigg writes about is the concept of keystone habits. For example, studies have shown that people who start the day off by making their bed, first thing, accomplish more and are more productive. This is a keystone habit. Others include eating dinner together as a family or exercising.

Keystone habits are:

- Doable

- Repeatable

- Relatively simple

- Have a cascading positive effect

Who doesn’t want success? “Cascading” sounds easy and pleasant. It doesn’t sound like pulling teeth or fighting resistance. But what can be some keystone habits for school change?

6 Keystone Habits OF innovative SCHOOLS

- Looking at Student Work

This involves taking out samples of student work, talking about what the learning goals were and assessing whether it was demonstrated. Next, we can determine what could be the next step for this student or a collectively move the teacher could have made to push their learning. This creates a culture of data analysis, critical collaboration, and best practice sharing. How else can we ensure that students are developing deep skills and working on rigorous content? It brings increased professionalism into education, similar to grand rounds with medical students. Also, you get the instant gratification of positive feedback and connection from your colleagues. Here’s a protocol.

- Staff Why and Staff Testimonials

This is a routine where staff share a story of a recent success, breakthrough, or recent learning. It can also take the form of staff sharing a bit of their personal story and their purpose of education. At my school, we began each Professional Development meeting with this. Before our learning, we got to hear someone’s story and their “why”. This helps to unite our staff by humanizing each person and underscores our collective purpose. It is easy to forget our mission when the rubber hits the road, or the proverbial milk carton hits the wall. It allows us to build on this foundation. Following a staff why, everyone claps and a little joy is released for the person who shares and the whole room feels a little bit of it. - Connections Protocol

This is an activity, where you sit in a small or large circle and have an open space for everyone to share what is on their mind. There are general guidelines to create space for everyone to be open, confidentiality, and a requirement of not responding. Silence is allowed. Open space is ok. No prompts are required. It allows people to be present and bridge where they are coming from to where they are. It facilitates listening. This habit creates stronger bonds and allows for people to be more ready for learning. In our school, it spread to our students, where we led students through connections in our Homerooms.

- Common Planning Time and Professional Learning Communities

Depending on what your school or district looks like, you have time for meetings. That might be business meetings (where did that term even come from) or Professional Development. In SFUSD, we have weekly CPT, also called Common Planning Time. The emphasis here is COMMON. This is a dedicated time to come together to do some things, which could be planning logistics, determining interventions for students, or sharing best practices. The habit here is it being a regular time, where folks collaborate. Leveraged well, it breeds further collaboration, lateral accountability, and the sharing of advice. It can break us out of the silos and might even lead to cross-curricular projects. At our school, this led to teachers integrating our students in sheltered English, general education, and special education. You might need to blow up your master schedule to create time for this. - Closing Celebrations

We have tried to end our meetings with a space for staff to celebrate each other. This might be a direct individual celebration such as, “Thanks to Teacher X for helping me plan my next project” or “thanks for watching my class so I could use the bathroom.” Or it could be general, “Shout out to the 8th-grade team for organizing a rock solid promotion ceremony!” Either way, its a space that generates oxytocin, reinforces positive behavior and builds community. It can even spread to the students. It is dedicated time to force us (later it feels much more organic) to be positive and look at the bright spots. - Eureka Moments

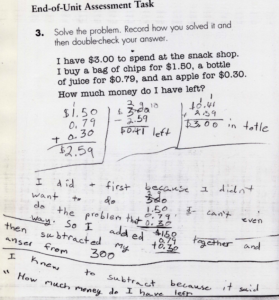

I observed this one while visiting John Muir Elementary School, for a math training that modeled Japanese lesson study. At the end of every math lesson, the teacher asks students to write down, in their notebooks, the biggest “aha” moments, and what they learned from today’s lesson. The teacher then reads them and selects 3 to write on the board. She starts the next lesson by reading those. This is a throughline from the previous lesson, it makes students thinking visible, and it breaks down concepts in student-friendly language. Furthermore, it puts students at the center of learning and celebrates those particular students. What if every class did something similar, in every school, in every city? Imagine. Boom.

KEYSTONE HABITS CAN BE BAD TOO

Don’t get it twisted. There are bad habits that we participate in every day that also communicate our values. We are not even aware of all them and since some were created before we arrived, we do not take responsibility of them. Some we did create but are not always aware of what they demonstrate. We can talk about school bells ringing every 50 minutes another time. These might be checking students’ uniform every day to see if they are “ready for learning.”

It might be circling names of late staff members in red ink, “to make a statement to the group.” Been guilty of this. A bad keystone habit could be requiring students to walk in silent, straight lines from one classroom to the next. A habit might be demanding teachers to turn in lesson plans every week, or checking standards on the board of all rooms, every day. You get the picture.

I realize there are different opinions on all of these, but I only suggest to consider what they say about your values and your assumption about of your students. Furthermore, I wonder which of these expectations (habits) would be used in predominantly white, suburban, and middle class or wealthy schools.

We need to analyze these and develop a counter activity.

Lessons Learned

- Sometimes habits develop organically, become sticky, and influence other change.

- It is ok to experiment a little, but give it time. Just because you do something once, or 5 times, doesn’t mean that it isn’t going to work. It takes time for the keystone habit to yield a larger change. I am still waiting for some.

- There are habits built into your school, department, or organization. You just have to think of how to shift them a little, which could shift big outcomes for students.

- You have to start small, like most things and give the rationale for the change. Remind your team that it will take time to see the results and impact. Remind everyone to trust the process. It is also a good practice to reflect on how this new practice has been going.

- Celebrate the small wins demonstrated through these habits and leverage them when its time to make bigger shifts.

- Use a protocol. The National School Reform Faculty has tons! This gives some structure to what might a vague and new experience for most people. It also removes you from being the facilitator and makes the process transparent. Practice whichever new process with low stakes content/material. You might even model it as a learning leader or you could ask one of your teacher-leaders to share a sample.

Conclusion

These keystone habits create an ether of what it means to be a member of your school, demonstrates your values, and can have a cascading effect on your environment. There is an oxygen that everyone breathes, and keeps everyone alive. This gas can become toxic as well, and only shifted through big and small change. Keystone habits and routines can do this. The task for culturally responsive leaders is figuring out which habits to set in motion, keeping them moving, and analyzing their consequences. We must determine the big change we want to see and shrink them into small, repeatable, habits. Rinse and repeat. 100 times and you are engineering for equity.

What are your school’s keystones habits?

Or what do you want to create a habit for?